This article, “Safe, secure, first. Finding a “golden mean” between innovation and regulation with self-driving vehicles” was written by Michael Talbot, Head of Strategy at Zenzic. It was published in the National Safer Roads Partnerships Conference brochure on Thursday 26 September 2019.

Watching BBC Click’s “The Self Driving Revolution” recently, I reflected on the tricky balance between innovation and regulation. I was reminded of the Roman poet Horace’s warning against “always pressing out to sea nor too closely hugging the dangerous shore”, advocating instead pursuit of a “golden mean” (I blame my misspent youth).

A famous example is Daedalus and Icarus. Daedalus makes wings from wax and feathers to escape from their captors; he warns his son to fly neither too close to the sun (or the wax will melt) nor too close to the sea (or the feathers will become waterlogged) but to steer a safe, secure middle course – a golden mean.

For me, these classical examples illustrate the difficulty of finding an ideal balance – a golden mean – between regulation and innovation. Regulate too early and we stifle innovation; too late and we risk disorderly deployment. And timing is irrelevant if we regulate badly. The Council of Science and Technology acknowledged this challenge in a 2015 letter to the Prime Minister, Capturing value in the autonomous and connected vehicles industry, which pointed to the timeliness of standards development for these technologies, “develop a standard too early and it may impede innovation, too late and others may already have done it.”

Self-driving vehicles could reduce 1.3 million deaths worldwide

The BBC programme explored a range of themes but focused on the testing Uber and Waymo have been conducting in Arizona and the regulatory environment that facilitated that testing. Perhaps predictably, Uber’s fatal incident in Tempe last year was examined in some detail – an event that sent shockwaves through the sector, including the UK’s burgeoning connected and autonomous vehicle development sector.

The incident emphasises the paramount importance of safety and public acceptance if we, as a society, will ever be able to enjoy the enormous potential of these technologies to make journeys safer, fairer and cleaner, securing as much as £52 billion for the UK economy by 2035 and reducing the 1.3 million deaths on the world’s roads each year – globally, the leading cause of death for people aged 5-29 years.

The safety imperative is borne out by research commissioned by the Department for Transport, which earlier this year published the latest in a “wave” of reports tracking the changes in attitudes to new transport technologies. For self-driving vehicles, safety is the most widely cited advantage of self-driving vehicles – but safety is also the most widely cited disadvantage.

Legislation: from horseless carriages to self-driving vehicles

In the UK, government has wrestled with the safe development and deployment of automotive innovation since before the advent of the motor car. The 1865 Locomotive Act (the Red Flag Act) famously restricted the speed of horseless carriages to 4 mph (2 mph in cities) and required someone to carry a red flag in front of the vehicle – effectively preventing any innovation until the 1896 Locomotives on Highways Act authorised speeds up to 14 mph (local governments could restrict this to 12 mph), raised again to 20 mph in the Motor Car Act 1903. The UK’s automotive sector blossomed.

Although there were other social and commercial interests at play, safety was at the forefront in these debates. For instance, the first campaign in 1917 by the London “Safety First” Council (now the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents) reduced fatal accidents involving motor vehicles and pedestrians by 70% in the first year.

Steady progress has been made to improve safety for road users with the result that the UK has some of the world’s safest roads. But, since 2010, the number of fatalities has broadly plateaued and an average of 5 people are killed and 75 seriously injured on our roads every day. With 85% of road collisions resulting in personal injury involving human error, automated vehicle technologies could save 3,900 lives and prevent 47,000 serious accidents by 2030. Several of these technologies (Automated Emergency Braking in particular) are already making a real difference.

Over that time, the UK has accumulated a global reputation for excellence in transport safety, enhanced by world class safety-focused organisations such as TRL, Horiba Mira, Millbrook, Thatcham Research, and Lloyds Register Foundation (see ‘important information’ below). This year has seen some great new UK contributions, most recently Roborace’s proposal of an “AV Turing Test” and CAT driver training’s creation of “the world’s first independent (accredited) autonomous safety driver training course”.

The steps being taken to ensure the UK remains a global leader

Given our deep history in transport safety, perhaps it isn’t that surprising that our government established an early reputation for global leadership in the regulatory frameworks around the safe development and deployment of self-driving technologies.

Recognising that regulation invariably lags behind the pace of innovation, the government’s Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CCAV) initiated a rolling programme of regulatory reviews in 2016, which builds on its world-leading Code of Practice (2015). The UK is the first parliament in the world to amend its primary legislation to facilitate the deployment of highly automated vehicles (the 2018 Automated and Electric Vehicles Act) which coincided with the start of the ongoing, safety-focused Law Commission review of automated vehicles.

In tandem with this regulatory work the government has allocated around £250 million (matched by industry) to the research and development and testing of future mobility technologies, building a virtuous cycle of virtual, controlled, and real-world (public) testing that spans more than 80 projects and over 200 organisations.

Given the speed and range of technologies and services being proposed around the world, the government’s initial approach has been to stimulate and grow the CAV ecosystem, accelerating and enhancing its capabilities, and then challenge the sector to develop use cases at scale. Created as part of this first phase of CCAV activity, Zenzic is playing an integral role in the next phase of work, bringing together government, industry, and academia to work out where the UK should focus its resources to ramp up and optimise the economic and social benefits, safely and securely.

This leads us to the UK Connected and Automated Mobility Roadmap to 2030

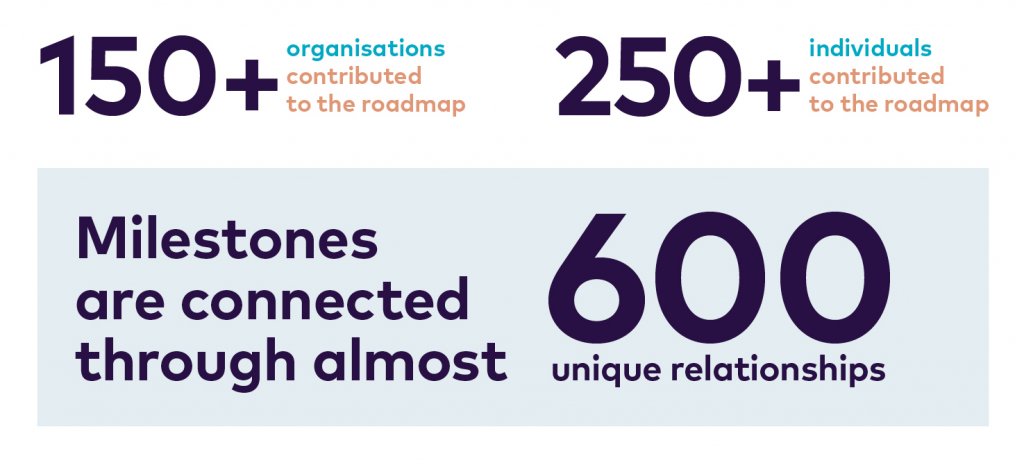

To this end, Zenzic recently published the UK Connected and Automated Mobility Roadmap to 2030. This tool provides direction for decision makers, investors and policy makers for the mobile future. The roadmap addresses developments from the present day to 2030, with a single vision of dependencies, investment needs and the path to scale capabilities and technologies. Safety is a specific “golden thread” that runs through the roadmap, which takes a technology neutral approach and was developed with more than 250 representatives from 150 companies and organisations across the key sectors [see chart], building on – rather than duplicating – existing work.

Guided by the 2030 roadmap and working with our partners in industry and government, we are confident that we will be in the best possible position to find the elusive golden mean and to maintain it, helping the UK to secure the support of the public for the technologies and the safest possible deployment of transformative new services, thereby unlocking the significant social and economic benefits.

Spencer Kelly, BBC Click’s host, described autonomous vehicles as “the hardest problem in technology – and one which could change everything”. He concluded by asking, “the question is not ‘if’ or ‘when’ this will happen, but ‘will we let it’?” With safety at the heart of our activities, and a commitment to engage in an open, evidence-based discussion of the merits and trade-offs of these promising technologies, I hope the answer will be “yes”.

2019: a banner year in UK self-driving safety initiatives

2019 has been a banner year for self-driving safety initiatives in the UK, building on what has become the global gold standard, the Department for Transport’s The Pathway to Driverless Cars: A Code of Practice for Testing (2015).

- The Government’s Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CCAV)

- published its Code of Practice: Automated Vehicles Trialling. Updating the 2015 code, it promotes responsible vehicle testing and details some safety recommendations, including the expectation of a safety case.

- started its CAV PASS project (Connected and Automated Vehicle Process for Assuring Safety and Security) which brings together Department for Transport teams (vehicle standards, cyber security, road safety, licensing) and Agencies (VCA, DVSA and DVLA) to start scoping a process for advanced trials of CAVs as indicated in the revised code. This work includes consideration of a future process covering commercial development, sale, and use of CAVs.

- In support of CCAV, Zenzic

- published its Safety Case Framework (authored by TRL), which is starting to develop a consistent safety approach across all testbeds, promoting best practice rather than minimum standards, and moving towards a single, portable safety case for each trial/vehicle to facilitate the transition between testbeds – and complementary to the approach taken by other stakeholders such as Highways England and Transport for London, among others.

- published its UK Connected and Automated Mobility Roadmap to 2030 which provides direction for decision makers, investors and policy makers for the mobile future. The roadmap addresses developments from the present day to 2030, with a single vision of dependencies, investment needs and the path to scale capabilities and technologies. Safety is a specific “golden thread” that runs through the roadmap, which was developed with more than 250 representatives from 150 companies and organisations across the key sectors.

- The Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission closed their preliminary consultation as part of a three-year review to prepare driving laws for self-driving vehicles, reviewing the UK’s regulatory framework to enable the safe and effective deployment of automated vehicles, and considering how safety can be assured both before and after automated driving systems are deployed.

- Roborace, the British autonomous motorsport company, established the Autonomous Drivers Alliance (ADA), a not for profit association which has proposed an international “AV Turing Test”, based on three principles, proving that the AI

- never engages in careless, dangerous or reckless driving behaviour.

- remains aware, willing and able to avoid collisions at all times.

- meets, or exceeds, the performance of a “competent & careful” human driver.

Important Information

|

HORIBA MIRA, established in 1946 as the Motor Industry Research Association, has over 70 years’ experience in developing some of the world’s most iconic vehicles. It has developed world class functional, passive, and active safety capabilities and has been developing autonomous vehicles since 2002, most recently through the HORIBA MIRA-Coventry University CAV Testbed, a track for automated vehicles to test at the limits of their controllability to ensure they are safe. |

|

TRL started in 1933 as the government-funded Road Research Laboratory, boasting Hugh Cardew, the “father” of British AV technologies with his remarkable 1960s AV projects. Most recently TRL is leading the Smart Mobility Living Lab to support public CAV testing in London as well as playing a key role in updating the EU’s General Safety Regulation, mandating the next generation of vehicle safety standards by 2022. |

|

Millbrook, opened in 1970 as General Motors’ Proving Ground; now independent with nearly 50 years of safety testing expertise. Millbrook is currently leading the Millbrook-Culham CAV testing facility offering the full spectrum of controlled to semi-controlled urban environments and 90 km of roads, enhanced by ground-breaking 5G capabilities. |

|

Thatcham Research, a ‘not for profit’ insurer-funded research centre established by the motor insurance industry in 1969, with the specific aim of containing or reducing the cost of motor insurance claims while maintaining safety standards. In 2016 Thatcham established the Automated Driving Insurers Group (ADIG) to support the Association of British Insurers (ABI) around the development of CAV technologies. |

|

Lloyds Register Foundation is a charity established in 2012 to protect the safety of life and property, and to advance transport and engineering education and research, publishing its Foresight review of robotics and autonomous systems in 2017 and, later that year, funding the £12m Assuring Autonomy International Programme (AAIP) based at the University of York. |